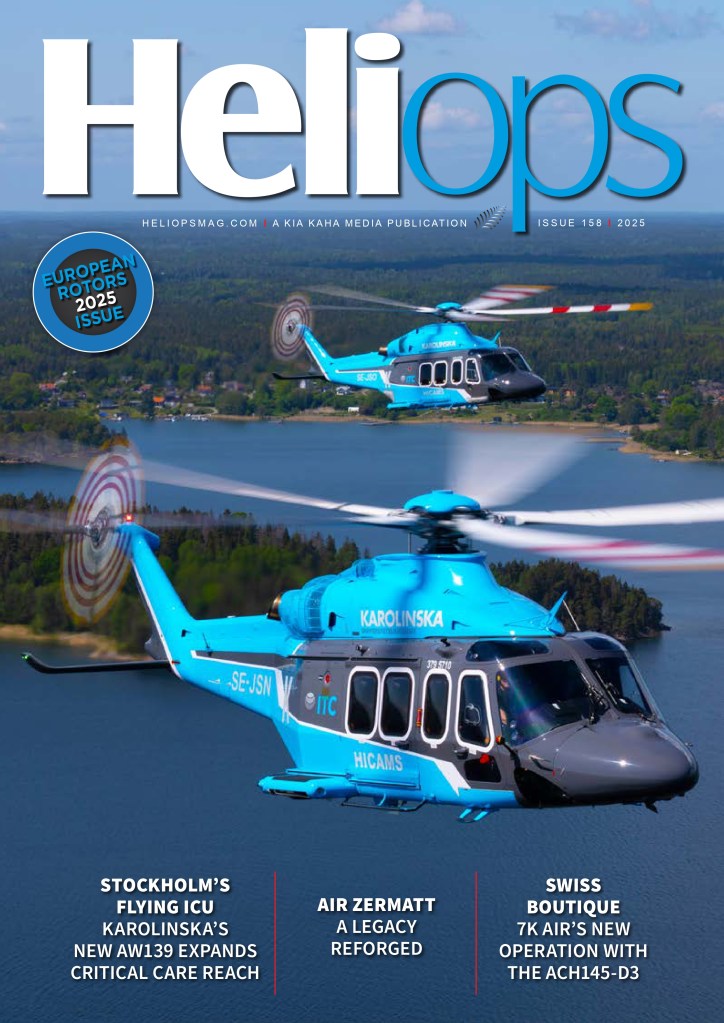

Adele Dobler didn’t grow up pining to be a pilot. “I admired airplanes and helicopters, but I didn’t see anyone who looked like me in the cockpit, so I unconsciously wrote it off as impossible.” That changed one summer in her early twenties when she was selling fruit by the roadside. “A woman came by for cherries, and when I explained how helicopters were used to blow-dry the crops, she casually replied, ‘Yeah, I do that.'”

That single sentence shook me. For the first time, I saw someone like me flying. I wish I had gotten her name and contact info, because she completely changed my life, and I never got the chance to say thank you!”

The true turning point came a few months later, when Adele was pinecone-picking in brutal -25°C weather. It is a random job, part of the silviculture industry, where pine cones are collected to sprout for the next tree planting season. “We would rummage around active logging sites to collect pine cones, fill a five-gallon pail, then fill a burlap sack to get paid per 80lb bag.”

“One day, after an exhausting and freezing cold day in knee-deep snow, the zip tie holding the top of the bag together broke, and I lost the entire contents of cones into a pile of felled trees I was clambering over.” Adele collapsed to her knees in frustration just as a JetRanger flew overhead. “That was the moment I decided I would change my life. My ‘why’ became clear: I wanted to be in that helicopter, not watching from the ground! And today, my deeper ‘why’ is to show up on someone’s worst day as a HEMS pilot, helping give them their best chance at tomorrow.”

Adele left university, scraped together money for a medical, and moved to Edmonton to take three jobs. She self-funded the entire thing. “I worked odd jobs doing barn chores, installing sewer pipes, selling beer at football stadiums, and driving pedicabs to pay for every flying hour. Scholarships from the Whirly-Girls organisation were a lifeline; they provided me with opportunities for specialised training, such as mountain flying and night vision goggle operations, that would have otherwise been out of reach.”

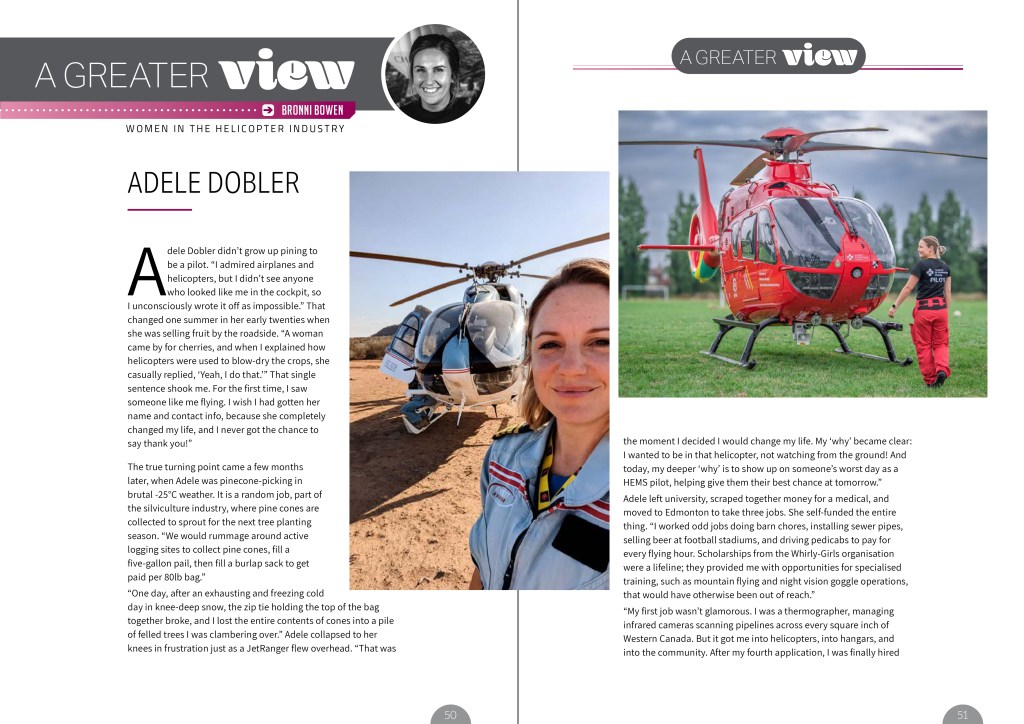

“My first job wasn’t glamorous. I was a thermographer, managing infrared cameras scanning pipelines across every square inch of Western Canada. But it got me into helicopters, into hangars, and into the community. After my fourth application, I was finally hired by my dream company at the time. There, I worked my way up into passenger service jobs and ground handling, then the opportunity to fly tours in a LongRanger, then multi-crew operations, until eventually I became the Lead Captain on the Sikorsky S-76.”

Adele admits there were challenges, of course. “Plenty. Early on, an instructor told me flying meant I’d never be able to have a family. Another pilot told me girls couldn’t lift fuel drums, and I’d never be hired. I totally believed them and accepted their version of the truth as my reality. What saved me was a conversation with a stranger while travelling in Indonesia. She simply said, “Who cares what he thinks?” It sounds small, but it flipped a switch for me, and from there, I was unstoppable.”

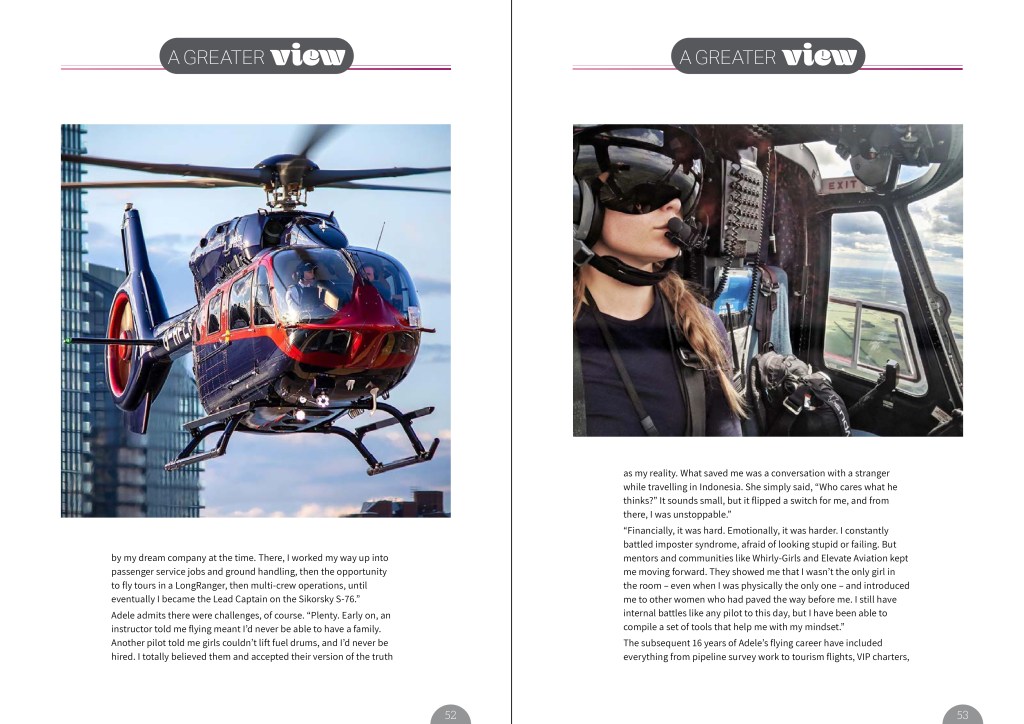

“Financially, it was hard. Emotionally, it was harder. I constantly battled imposter syndrome, afraid of looking stupid or failing. But mentors and communities like Whirly-Girls and Elevate Aviation kept me moving forward. They showed me that I wasn’t the only girl in the room – even when I was physically the only one – and introduced me to other women who had paved the way before me. I still have internal battles like any pilot to this day, but I have been able to compile a set of tools that help me with my mindset.”

The subsequent 16 years of Adele’s flying career have included everything from pipeline survey work to tourism flights, VIP charters, scheduled passenger service, and HEMS/air ambulance operations – mostly full-time, too. “I spent six years with Helijet in Vancouver, where we had a diverse mix of work with the Air Ambulance contract, flying out to remote fishing lodges in Northern British Columbia, as well as Scheduled Passenger Service flights.” Following this, Adele achieved her long-held dream of joining STARS in Alberta as a HEMS pilot, flying her first job with night vision goggles (NVGs).

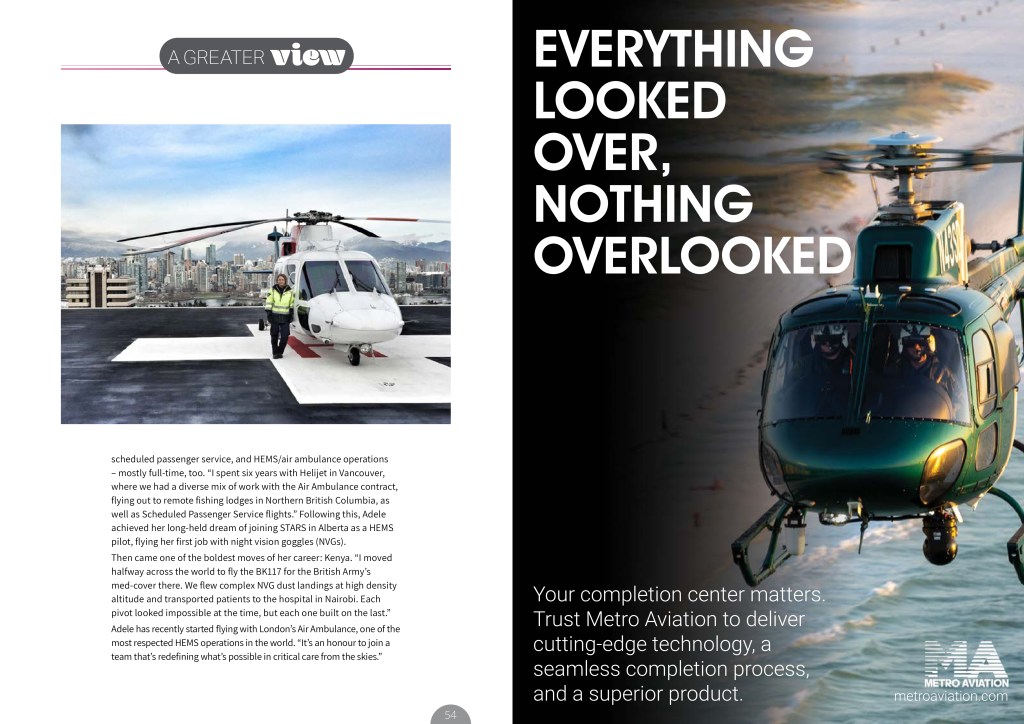

Then came one of the boldest moves of her career: Kenya. “I moved halfway across the world to fly the BK117 for the British Army’s med-cover there. We flew complex NVG dust landings at high density altitude and transported patients to the hospital in Nairobi. Each pivot looked impossible at the time, but each one built on the last.”

Adele has recently started flying with London’s Air Ambulance, one of the most respected HEMS operations in the world. “It’s an honour to join a team that’s redefining what’s possible in critical care from the skies.”

“The best days are the ones where I wake up knowing that by sunset, someone’s life might look different because of our flight.” A typical HEMS shift might mean launching from the roof in central London, then landing in a snug spot in the middle of the city surrounded by cranes, tower blocks, and people. “We have to balance the importance of why we are flying while mitigating the risks of landing in such a busy, densely populated city. At the end of a long day, I’m exhausted but deeply grateful for the work I am able to do. I crawl into bed knowing I’ve given everything, and there’s no better feeling.”

Adele agrees that cost is a prohibitive factor for aspiring pilots – everybody has felt this, particularly in recent years. She says government-backed student loan programs or structured apprenticeship models might open doors for more people – but it’s not the only pressing issue she observes in the industry.

“Culturally, I’d like to see a shift in how we support stressed-out, overworked pilots. Fear of losing a medical certificate, and therefore their career, keeps pilots from seeking help when they need it and before things get out of control. There are peer support resources, but very few pilots reach out to talk to someone for fear of being ‘found out’ or deemed unfit to fly. Unfortunately, we are all aware of the consequences that occur when these issues are left unchecked for too long. How can we remove the stigma and offer the necessary emotional support to crews while maintaining safety in the cockpit?”

Adele is clearly passionate about mentoring and supporting aspiring pilots, doing so via organizations like the Whirly-Girls and Elevate, and even her own inspiring Instagram channel. “I’m working on releasing a number of guides that offer quick wins for pilots to help with mindset and addressing some of the challenges we all face in the industry.”

“I owe a lot to the women who came before me, aviators like Jennifer Murray, Jean Ross Howard-Phelan, and Sally Murphy. They built the rungs of the ladder we now get to climb. The Whirly-Girls community has also been invaluable; their scholarships and mentorship have literally changed the trajectory of my career.”

When asked about highlights, Adele says nothing compares to seeing the Northern Lights over the Rocky Mountains on night vision goggles, or having a hyena steal one of your cyalumes while practicing dust landings in Kenya! And rocky bottoms? “I’ve had my share, from engine failures over open water to the crushing self-doubt that comes with imposter syndrome. But–” she is quick to point out, “Each low point becomes part of the foundation I stand on today.”

Adele plans to keep flying HEMS for as long as possible and advance within the company; it’s the most meaningful work she knows. “And, I hope to continue mentoring the next generation of women in aviation and give back to my community, so that one day, a girl won’t have to wonder if she belongs in the cockpit; she’ll just know she does.”

First published in HeliOps Magazine Isse 158