As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a helicopter pilot.

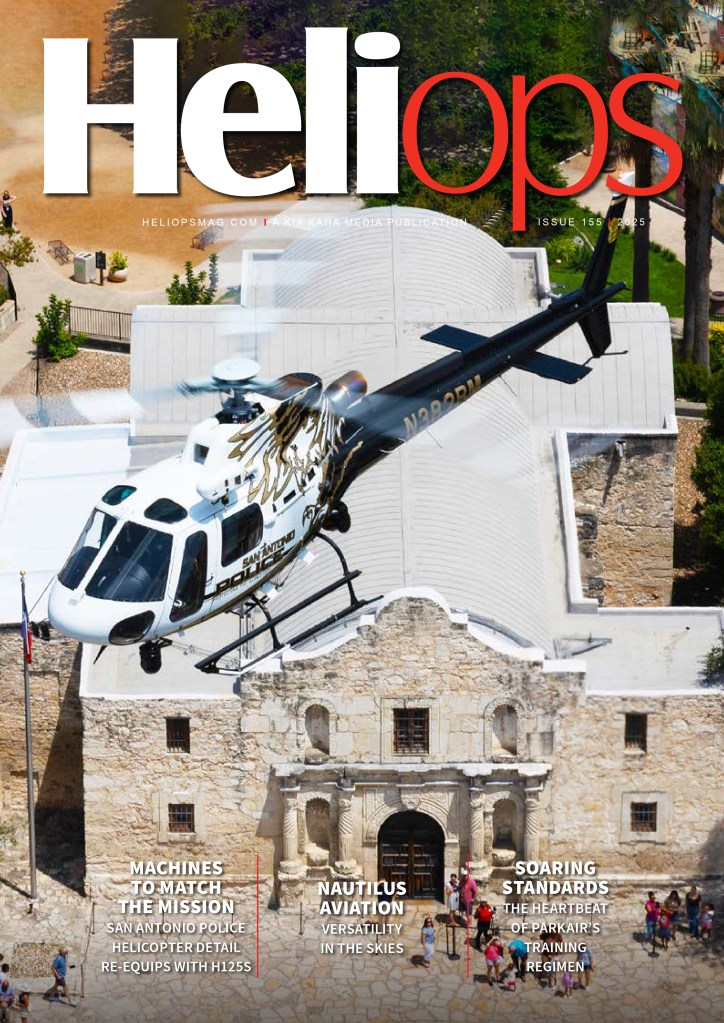

Justin Pedersen was 11 years old, at a friend’s house for an afternoon in the summer. The friend’s older brother had embarked on a career as a helicopter pilot, but at that age, it didn’t really click what that meant. Growing up on a cattle ranch in rural Northern Alberta, Canada, without any connection to aviation, someone being a ‘pilot’ meant about the same to the boys as a ‘truck driver’ or ‘crane operator.’ Until that point, Justin’s only exposure had been the occasional STARS air ambulance helicopter flying over (they were the bright red ones, he knew that) and the odd military machine on training missions in the area (they were the dark-colored ones, and they would spook the cows)!

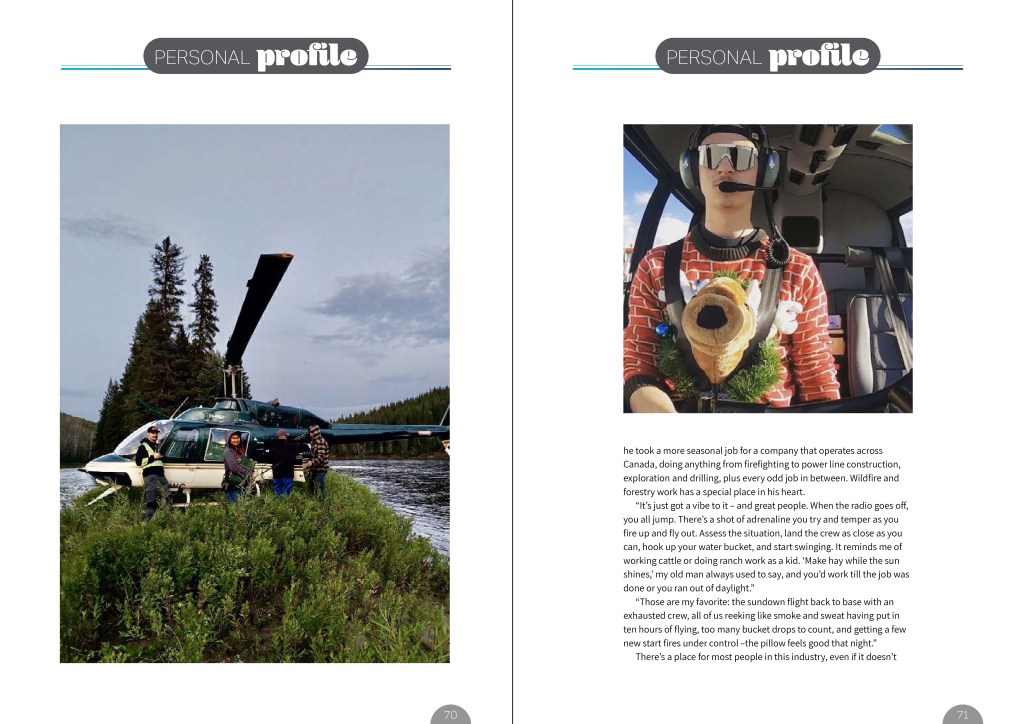

But that summer day, while goofing around with his friend, they heard a helicopter. Then, through the front windows of the farmhouse, they saw an R44 lower down and land on the front lawn! As luck would have it, the older brother was time-building in a private R44 and had gotten permission to stop in and give the family a short tour – an opportunity Justin jumped at.

“I don’t remember much about the flight, to be honest. I remember the radio squawking, and I remember not having the mic close enough to my mouth to talk. But – like it was yesterday – I remember looking at the blades of grass on the lawn blowing around in the downwash. In seconds, as we lifted off, it turned to a green mat of color, which turned to a green square in front of a house in the middle of a field, AND THEN I COULD SEE THE ENTIRE FIELD!”

“Without hyperbole, that feeling ruined me for life. I had to be a helicopter pilot.”

Anything worth doing is worth doing completely.

BB: How did you get going in the industry?

Justin: As I got older, I became increasingly focused on being a helicopter pilot.

I joined the nearest Royal Canadian Air Cadet squadron just to get closer to aviation as a whole, and thanks to them, I was able to go on another helicopter tour flight that only reinforced my goals.

By age 16, I had found out the hard truths I think everyone does when eyeing up the industry; you’re not gonna get rich doing it, it’s not going to be like any other job out there, it’s going to take a long time and a lot of work to get started, and it’s going to be EXPENSIVE.

At the time, there were no specific student loans for pilot training in Canada, and with no money around to beg, borrow, or steal, working for it was the only option.

By 17, I was working full-time and had built a well-paying career in a separate industry, but I was arranging everything for when the time was right. During that time, I was told about a small flight school West of Calgary, Alberta, that had a program to hire some of the students out of each training class and give them work flying the R44 TV/Radio news helicopters across Canada (a rare opportunity to fly right out of flight school). So I moved close to that school.

Finally, after years of work, I quit my job and started flight training.

I did a full-time course over six months, all on the R44. It was way different than anything I’d ever done; it was challenging and frustrating, but boy, was it fun.

I remember having a hard time sleeping; I’d be too excited thinking about the flight that day or the flights I had scheduled for the next day. I’d hang out at the school all day, even if I didn’t have any flights or classes. I jumped at any opportunities to come in on weekends or holidays. This was a dream coming true, and I was 100% there for it.

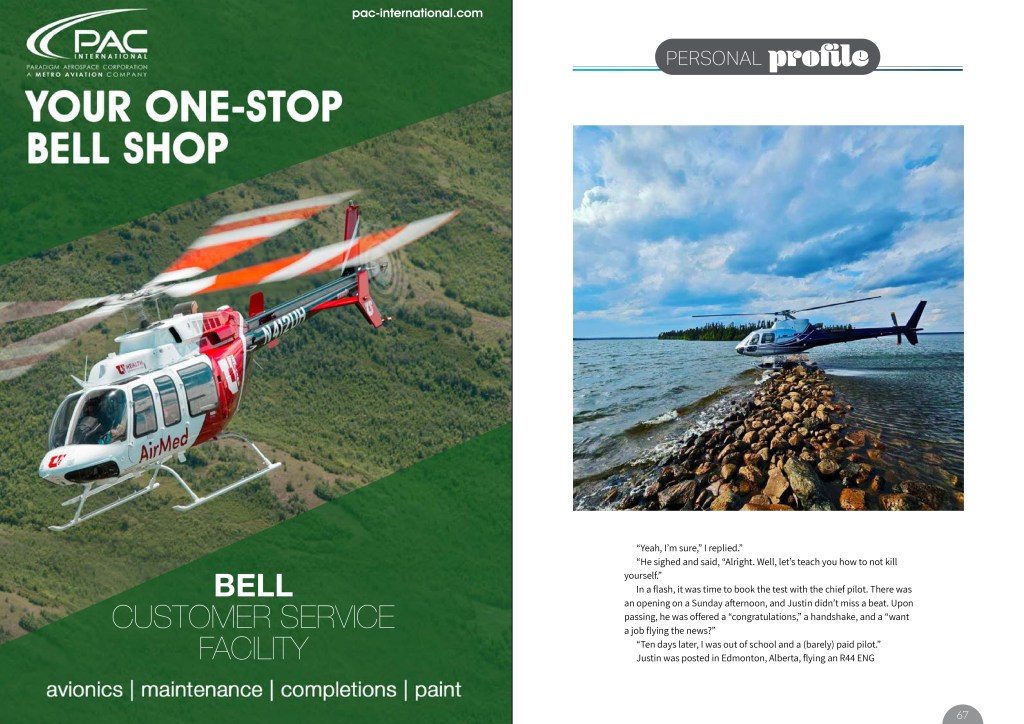

In a flash, it was time to book the flight test with the chief pilot of the school. There was an opening on a Sunday afternoon, and I didn’t hesitate to take it. I managed to be the first in the class to take the flight test, and upon passing, I was offered a “congratulations,” a handshake, and a “Want a job flying the news?” from the chief pilot.

Ten days later, I was out of school and a (barely) paid pilot. I was posted in Edmonton, Alberta, flying an R44 ENG (electronic news gathering) set-up for the first year, then moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, for another year and a half.

After two and a half years and about 1250 hours, it was time to get out into the bush.

I’ll never claim to be the smartest or the most skilled pilot in the room. But I’ll make sure I’m the hardest working.

BB: What obstacles or assistance did you have?

Justin: This industry isn’t for everyone. I think you have to be a particular type of person and a little bit crazy to get into the helicopter business, especially for the VFR bush flying that interests me. But more than anything, I believe that to make a career of this, you have to have a passion and a drive for it. It’s a rough road full of challenges to get going and make it, and it’s not worth it unless you have a drive inside of you that makes you NEED to do this.

So, in a way, the challenges you face are how the industry is largely self-weeding – of the ones that think it’s ‘just another day job’ or ‘seems kinda cool.’

So, I guess in answer to the question, I’ve had my share of challenges and difficulties, but I’ve never blinked. Even on the worst days I’ve had, I still wouldn’t think of doing anything else. A few things that surprised me:

- How much of a people industry this is. Both with clients and colleagues in the industry, it’s a small world, and how you carry yourself really matters.

- The learning NEVER stops. You can be the expert in one area or one type of flying and completely clueless at the next – and that keeps it interesting!

- Balancing work/life can be the hardest part of the job. It’s a demanding, dynamic career unlike any other, and that can be difficult for people outside the industry to understand – or for a young pilot to wrap their head around going into it.

An instructor I had in flight school was the best at giving the ‘hard truths’ and lessons about flying and the industry. I’ll never forget my first flight with him; it was essentially 30 minutes of him trying to convince me I didn’t want to be a pilot: “You’re going to be working away from home all the time, so … you can’t have a dog”, “you could make a lot more money doing something else, you know,” “you’ll be working in the heat all summer and the cold all winter so I hope you like that,” and on landing asked, “so? You still want to do this? Not too late to back out now and go live a happy life”.

“Yeah, I’m sure,” I replied.

He sighed and said, “Alright. Well, let’s teach you how to not kill yourself.”

That instructor painted a very brutal but real picture of life as a helicopter pilot (and I’ll always be thankful for that), but also said he’d never think about doing anything else. I learned a book or two’s worth from him.

BB: What has your career been like?

JUSTIN: Well, as I said above, I started as a TV/Radio news pilot, and looking back, it was a great time, although not without its share of challenges. The pay was about as low as you could go, so I worked three jobs to make ends meet and pay off any extra bills from flight school. The work was repetitive, flying circles around a car accident during the morning commute or a house fire in the afternoon, but the learning curve didn’t slow down for a while after flight school. Crew resource and cockpit management are paramount to heli-mounted camera work. Flying in controlled airspace all day, every day, in some of the busiest airspaces in Canada. And we were flying every day.

It was a great time to build the basic pilot skills and decision-making that are so important, and the lessons I learned I carry with me to this day.

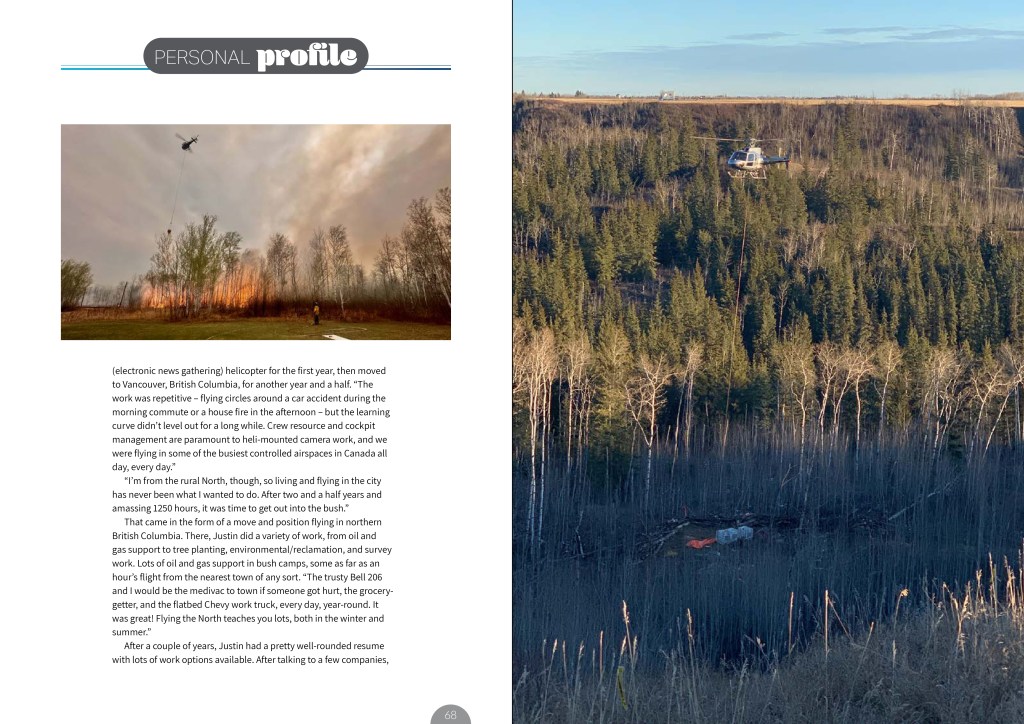

I’m from the rural North, though, so living/flying around the city has never been what I wanted to do. So, after two and a half years of that, I was looking for the next step. That came in the form of a move and position flying in northern British Columbia. There, I did a variety of work, from oil and gas support to tree planting, environmental/reclamation, and survey work. Lots of oil and gas support in bush camps, some as far as an hour’s flight from the nearest town of any sort, so the helicopter role was broad. The trusty Bell 206 and I would be the medivac to town if someone got hurt, the grocery-getter, and the flatbed Chevy work truck, every day, year-round. It was great! Flying the North teaches you lots, both in the winter and summer.

The work was super busy, and the amount/consistency of flying was nothing like I’d ever had. Four to six-week shifts, hitting maximum flight hours allowed, working long days, it was awesome.

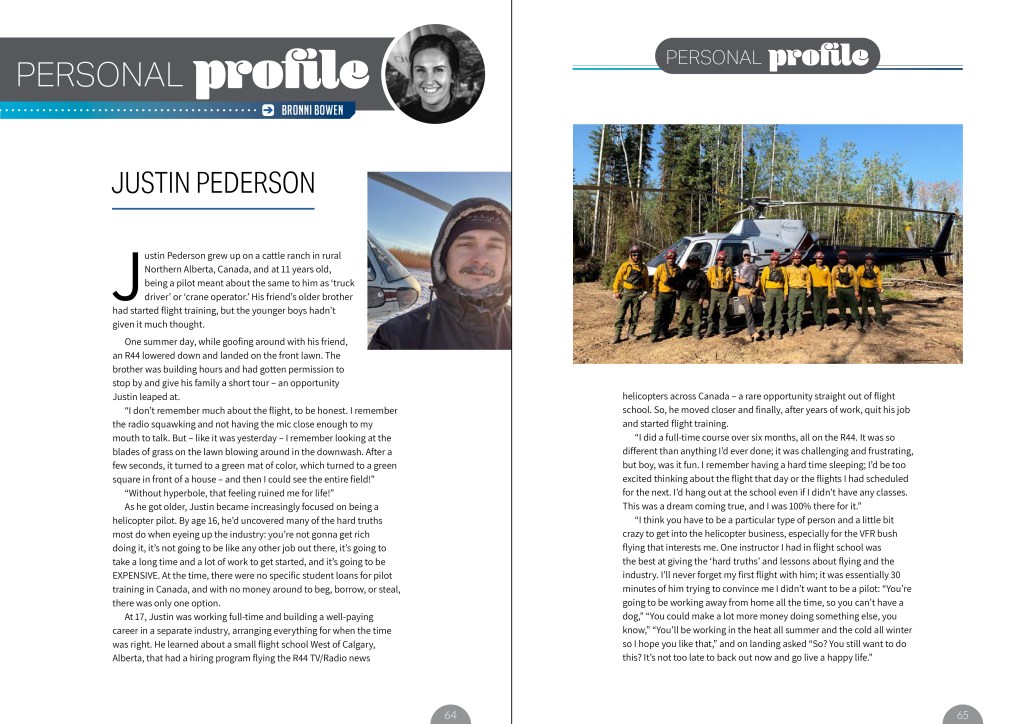

After a couple of years of that, I had built a pretty well-rounded resume with lots of work options available. After talking to a few companies, I took a more seasonal job for a company that operates across Canada, doing anything from wildfire fighting to power line construction, exploration/drilling, and every odd job in between.

I’ve always been a year-round, full-time guy, but now I am happy with a slightly slower winter season to catch up with life after a long summer season. There’s less winter work in Canada, but you can still stay busy all year if you want.

It takes a few years to build up a resume that puts the power in your hands and gives you options for work, but there’s lots of work, and the demand for experienced pilots is definitely there.

It’s been one adventure to the next, and that’s just the way I like it.

Fly as much as possible!

BB: What do you do now?

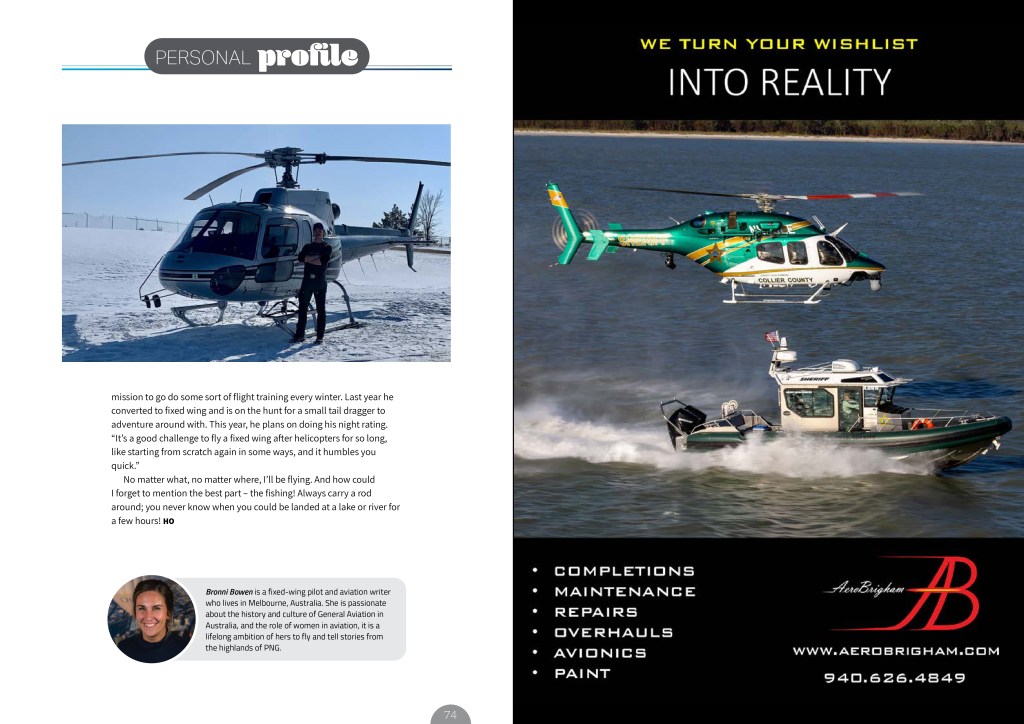

Justin: I’ve been flying AStars for the last couple of years, and there’s no shortage of jobs for them. They’re such a crazy, capable machine with so many jobs or roles it can step into.

After the last couple of busy fire seasons in Canada, the winter’s slower pace is good for catching up at home and spending some time with family/friends. That said, I tend to go a little stir-crazy if I don’t fly for more than a couple of weeks, so I’ve made it a mission to go do some sort of flight training every winter, and last year, I converted to my private fixed-wing license. I’m currently in the market for a small tail dragger to adventure around with. This year, I plan on doing my fixed-wing night rating. It’s a good challenge to fly a fixed-wing after helicopters for so long, like starting from scratch again in some ways, and it humbles you quick.

MakIN’ hay while the sun shines.

BB: What do your days involve?

Justin: To be honest, you never really know! This is a great part of this job – if you’re the type of person who can operate that way. Starting a three-week shift that gets turned into a six-week one is a challenge I actually enjoy (most times).

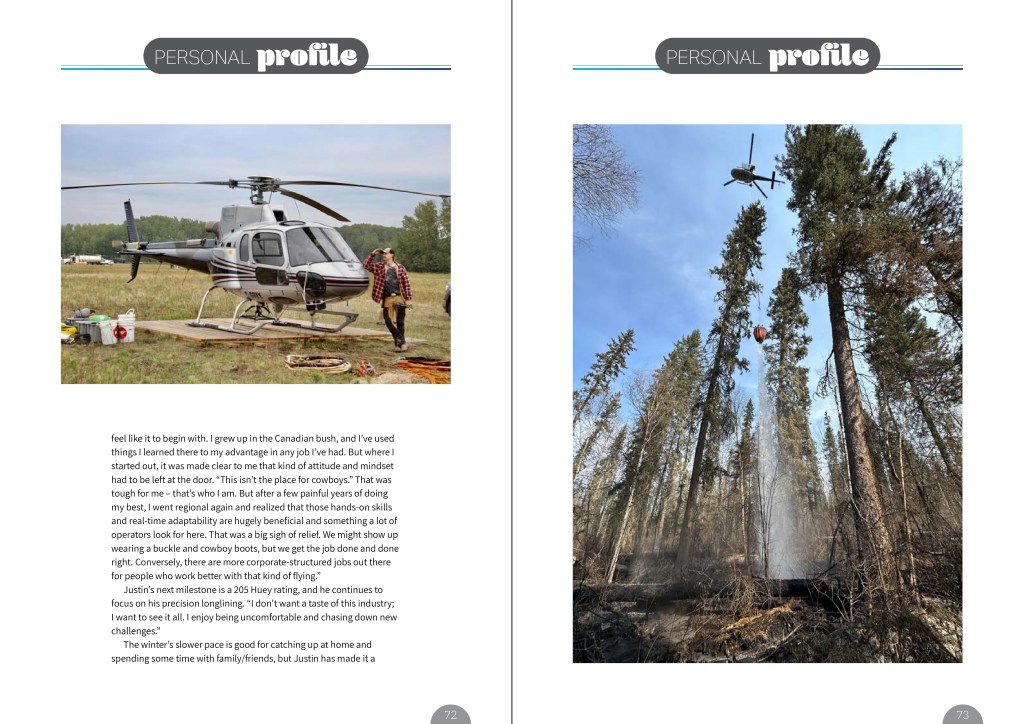

Wildfire/forestry work is some of my favourite. It’s just got a vibe to it, and great people. In Alberta, we have helicopters on call with a four-person crew, called Initial Attack, for a quick response to fire calls. Usually, you sit on a five-minute call-out time if the fire risk is high, so you hang out with the crew near the machine – and when the radio goes off, you all jump. There’s a shot of adrenaline you try and temper as you fire up and fly out; assess the situation, land the crew as close as you can, hook up your water bucket, and start swinging. It’s really hand in hand with your crew, and by jumping on it early, every minute is a higher chance of getting it under control or extinguished by sundown, and lots of times, that’s how late it goes.

It reminds me of working cattle or doing ranch work as a kid. ‘Make hay while the sun shines,’ my old man always used to say, and you’d work till the job was done or you ran out of daylight. With that work ethic engrained in me, those are my favorite days. The sundown flight back to base with an exhausted crew, all of us reeking like smoke and sweat – having put in ten hours of flying, too many bucket drops to count, and getting a few new start fires under control – that’s a great day.

One memorable day, I was in northern Canada working with a couple of crews, mopping up a smoldering fire. On the flight back to base around 5 pm, we found a new fire at a small village; it’d already burned through three houses and was on the front porch of the fourth. I dropped my crew, hooked up my bucket, and took off. With the time of the day and the remote nature of the location, we had no other helicopters able to make it there in time to help, and more ground crews were hours away. I flew until last light and dropped over 100 bucketloads of water. We limited the fire to only taking those houses and landed at the base with 12 hours of fight time for the day.

The pillow felt good that night.

I try to take moments where I can after a busy day like that to pause and appreciate the dream job that came true, let it all sink in, and plan for the future.

BB: ANY changes you’D like to see?

Justin: Mm, good question.

I think (in Canada at least) the helicopter industry is caught between the old-school way things have always been done and adapting to the way the industry is NOW. There’s a balance between the two that most operators haven’t found yet. I think the more that gets fine-tuned, the fewer issues we’ll have with pilot demand and progression for young pilots. Also, the demand for pilots and engineers isn’t helped by operators refusing to recognize how important culture is in a company. I’ve stood in hangars with very good and very bad company cultures, and the difference is shocking. However, it takes a lot of work on the management’s side to foster a good company culture and maintain/attract new staff.

Never underestimate how much you can learn over a couple of beers.

BB: Have any other individuals influenced you or … any comment on people and culture in the helicopter industry? Alternatively, are there any highlights or rocky bottoms you’ve experienced during life you feel you’d like to share?

Justin: I guess I answered some of these above, but there are a lot of culture and mentality changes I’d like to see in the industry. I believe it’s the responsibility of experienced pilots to pass along advice and information to younger ones. It’s also the responsibility of younger pilots to get good at asking for it. The culture of ‘well, no one helped me, so I won’t help anyone’ is counterproductive and is slowly going away. There’s already a lot in this business you have to learn for yourself, so why not help make that learning curve better and safer? A little mentorship goes a long way, and operators with a better mentorship program in place reap the rewards in staff retention and better company culture.

I don’t know about a ‘rocky bottom,’ but something that took me a while to learn is that there’s a place for most people in this broad industry. I grew up in the Canadian bush, and I could use things I learned there to my advantage in any job I’ve had. But when I started flying in a more ‘corporate’ kind of setting, it was made clear to me that kind of attitude and mindset had to be left at the door. “This isn’t the place for cowboys.” That was tough for me – that’s who I am. But after a few painful years of doing my best, when I got out of the city and started working in the bush, there was a moment of realization that those hands-on skills and ‘adapt to whatever gets thrown at you’ attitude are hugely beneficial, and the kind of capabilities these operators were looking for. That was a sigh of relief – that there’s definitely a place in this business for people like me. We might show up wearing a buckle and cowboy boots, but we get the job done and done right. Conversely, there are more corporate-structured jobs out there for people who work better with that kind of flying.

As for influences, there have been a couple of mentors who have received a panicked text from me with questions before going on a new job, etc. The one that’s been there the most is the one that started it all: my friend’s brother, who took me up for my first helicopter flight 17 years ago; the flight instructor who taught me how to fly and some of the hard lessons about the industry; and all the pilots I’ve worked with along the way, who like to sit down after a day of flying, have a beer and talk helicopters, techniques, tips, and swap stories.

I don’t want a taste of this industry; I want to see it all.

BB: What are your hopes for the future?

Justin: Keep flying and keep learning. Precision longlining is my current focus at work. My next goal is to get my 205 Huey rating and get some time on those incredible machines. It’s been a dream of mine to fly them since I was a kid. But beyond that, I think there’s WAY too much cool stuff to do and see in this business to be content with just a little piece of it. I enjoy being uncomfortable and chasing down new challenges, and there are plenty of those in this line of work. As the chief pilots and ops managers of the future, I think this generation should work hard to learn everything we can about both flying and the industry so that when we’re in those management or mentorship roles, we can help steer the industry in the right direction. It’s our responsibility to pass it on to those coming up through the ranks.

This summer (work schedule permitting), I’d like to get my skydiving license – something I’ve done a half-dozen times and would like to do more of! Hopefully, I will buy a plane soon and do more private fixed-wing flying!

No matter what, no matter where, I’ll be flying, though. And how could I forget to mention the best part of the job… the fishing! Always carry a rod around; you never know when you could be landed at a lake or river for a few hours!

Abridged version first published in HeliOps Magazine Issue 155 (complete with incorrect name spelling – sorry Justin!)