It’s early summer in Australia, and Jeremy Smith is spending the night out at Maningrida, a remote outpost on the coast of the Northern Territory. He’s just rolled his swag out on the floor of a community building after a big day in the bush with the rangers. The last few days have been spent fighting early-season fires started by a rogue bolt of lightning.

He’s stoked this evening because the room he’s sleeping in has air conditioning. “Sometimes in the fire season, we can be camped out bush for weeks, with a swarm of mosquitoes and an esky of food; if your food runs out or your ice goes, you could be doing it pretty tough for a while!” As he steps outside to show me the fleet of boats and maintenance vehicles, his neck glistens with sweat. Ninety-nine percent humidity is the norm at this time of year. “It can be sweltering, and sometimes people are delayed, too, so you might be waiting around for another few days,” he drawls.

“But it is good. It’s bloody good.”

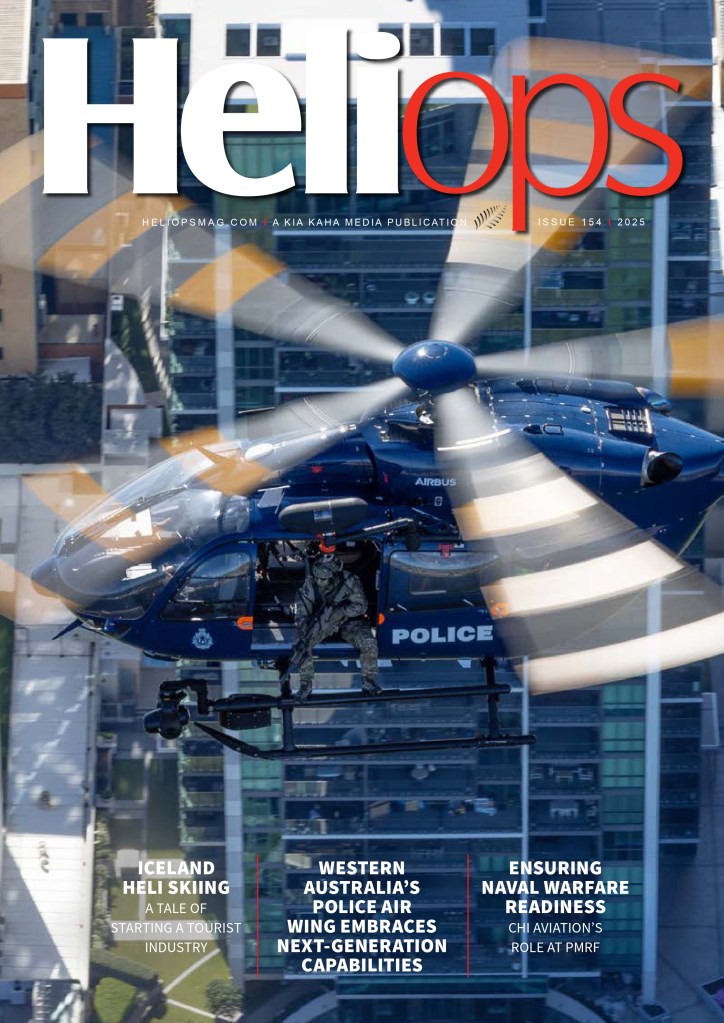

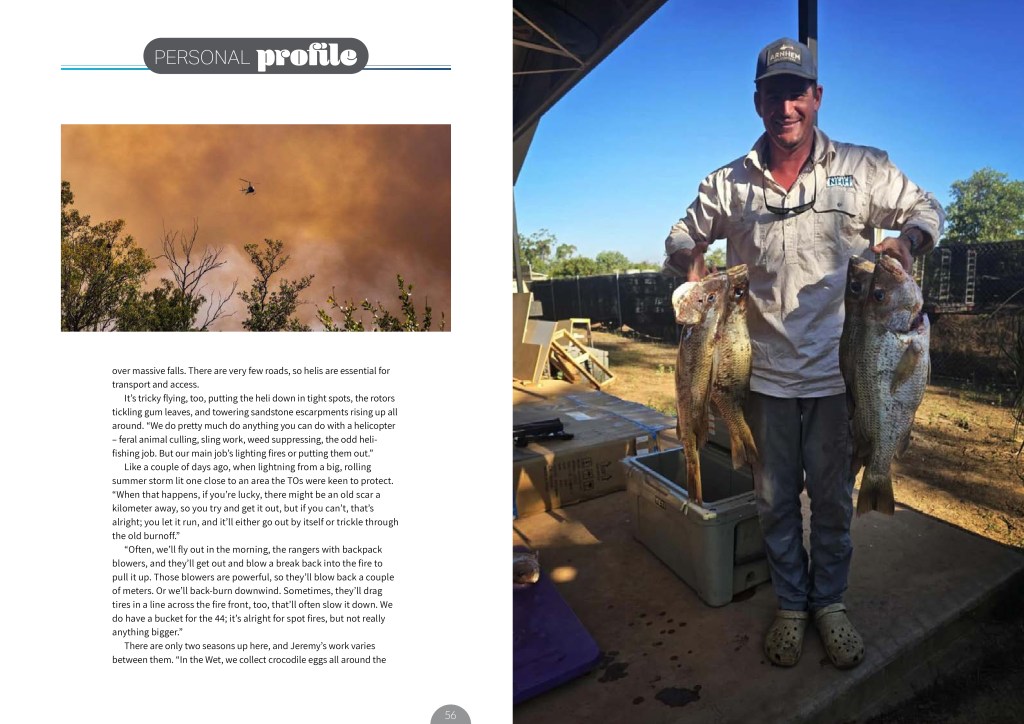

Jez is the picture of a Northern Territory heli pilot. Tall, tanned, and perfectly at home in his bone-coloured workshirt, a pair of Crocs on his feet, and an Arnhem Helis cap pushed back on his head, he’s a mad keen fisherman and hunter – fortunately, quite capable of sourcing his food if required. Being here suits him down to the ground.

At 16, boy Jeremy fled school and headed straight Outback to a station in far southwest Queensland called Nockatunga. “That’s a 2.2 million acre cattle property. The biggest paddock was a quarter of a million acres – so, as you can imagine, mustering by ground wasn’t going to cut it,” he chuckles. “As soon as I saw the choppers in action, I’d look up and think, ‘Gosh, how good would that be?’ I always thought that would be much better than being down here on a horse and bike.”

“When I finally got to go up in one for the first time, I was hooked. I always wanted to do it – always – and it was just the money. I just couldn’t.”

Eventually, Jeremy turned 28, thought, ‘Stuff it,’ and began casual flying lessons, driving trucks and saving all his money to put into flight hours. He soon realized it was going to be impossible to work and study at the same time. Airwork Helicopters, a flying school just north of Brisbane, suggested a government loan pathway through TAFE, and Jez seized the opportunity.

It wasn’t easy, but he gritted it out over 12 months, learning to study and slowly but surely passing one subject at a time. “I ended up moving out of the classroom and setting a little desk in the corner of the hangar to study at my own pace. At times, I thought I was never going to get there – but in the end, I did! I banged out my final hours and passed my CPL flight test. That was a big relief and definitely a memorable milestone in my life.”

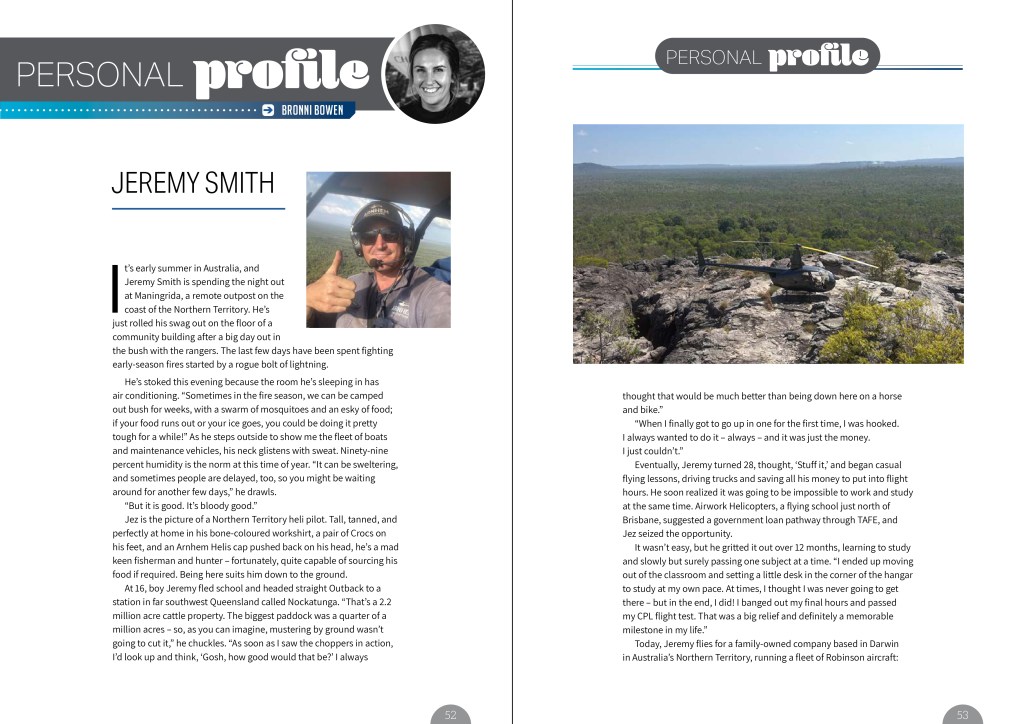

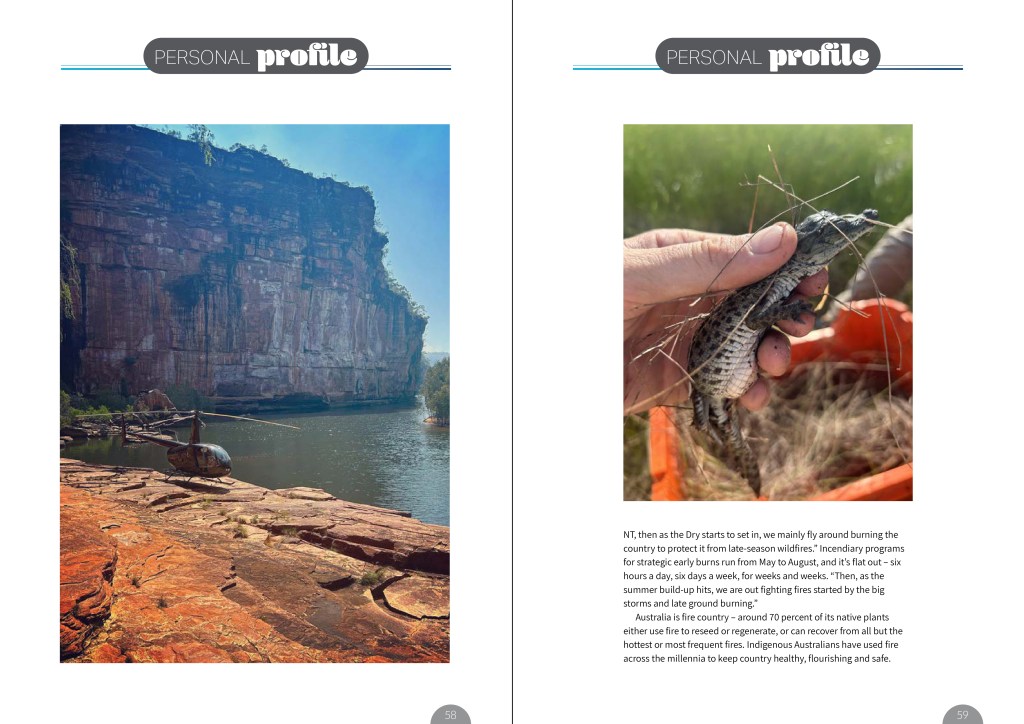

Today, Jeremy flies for a family-owned company based in Darwin in Australia’s Northern Territory, running a fleet of Robinson aircraft: three R44s and one R66. Arnhem Helicopters services the whole of Arnhem Land, working alongside Traditional Owners and rangers of different local groups and clan states. It’s all Aboriginal land, and the landscape varies dramatically – everything from savannah woodlands to stone country; big, steep gorges with megaliters of water flowing over massive falls. There are very few roads, so helis are essential for transport and access.

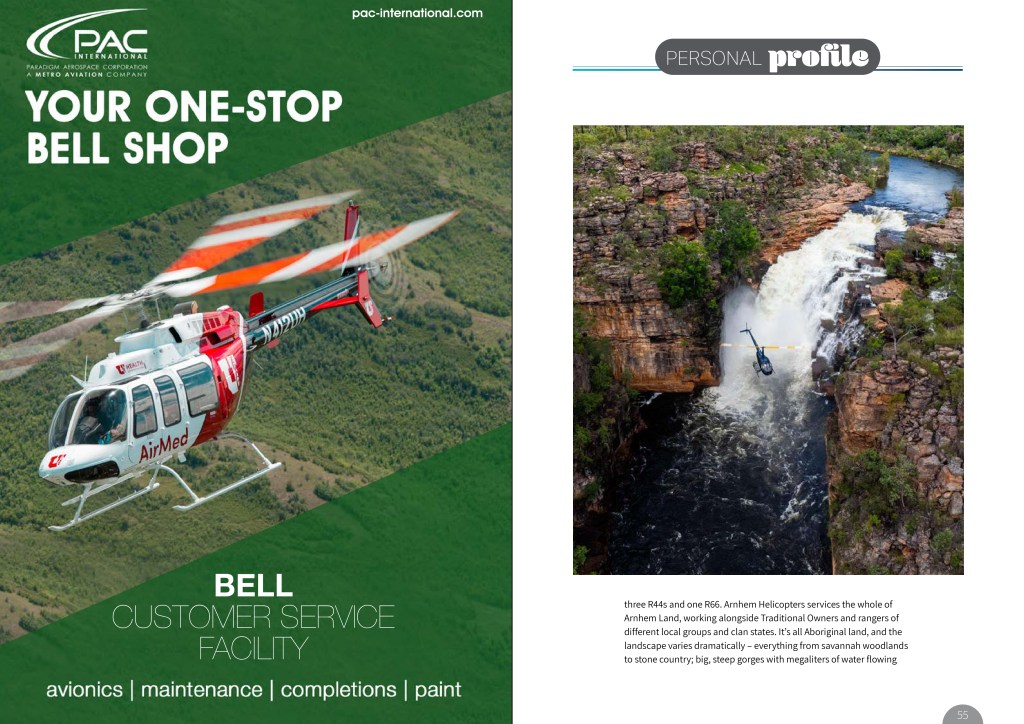

It’s tricky flying, too, putting the heli down in tight spots, the rotors tickling gum leaves, and towering sandstone escarpments rising up all around. “We do pretty much do anything you can do with a helicopter – feral animal culling, sling work, weed suppressing, the odd heli-fishing job. But our main job’s lighting fires or putting them out.”

Like a couple of days ago, when lightning from a big, rolling summer storm lit one close to an area the TOs were keen to protect. “When that happens, if you’re lucky, there might be an old scar a kilometer away, so you try and get it out, but if you can’t, that’s alright; you let it run, and it’ll either go out by itself or trickle through the old burnoff.”

“Often, we’ll fly out in the morning, the rangers with backpack blowers, and they’ll get out and blow a break back into the fire to pull it up. Those blowers are powerful, so they’ll blow back a couple of meters. Or we’ll back-burn downwind. Sometimes, they’ll drag tires in a line across the fire front, too, that’ll often slow it down. We do have a bucket for the 44; it’s alright for spot fires, but not really anything bigger.”

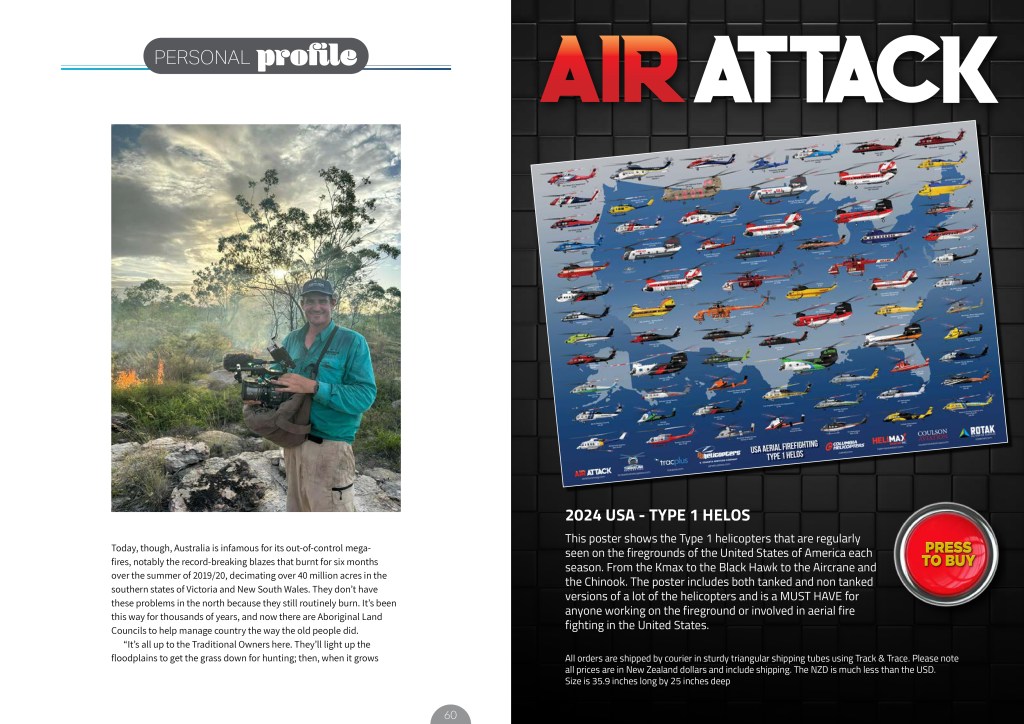

There are only two seasons up here, and Jeremy’s work varies between them. “In the Wet, we collect crocodile eggs all around the NT, then as the Dry starts to set in, we mainly fly around burning the country to protect it from late-season wildfires.” Incendiary programs for strategic early burns run from May to August, and it’s flat out – six hours a day, six days a week, for weeks and weeks. “Then, as the summer build-up hits, we are out fighting fires started by the big storms and late ground burning.”

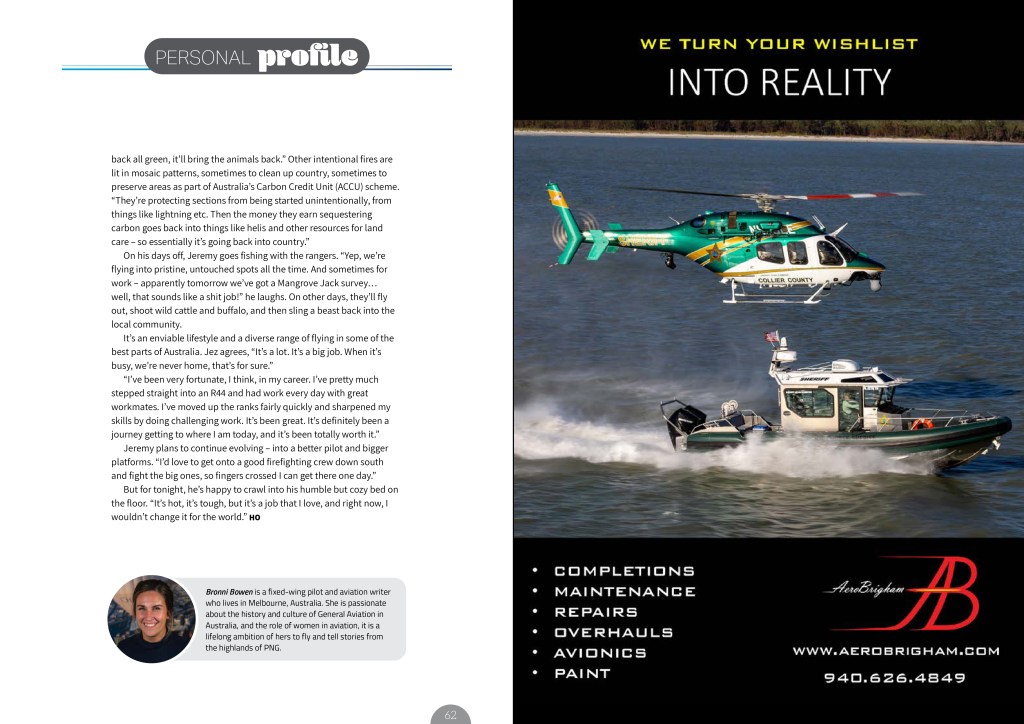

Australia is fire country – around 70 percent of its native plants either use fire to reseed or regenerate, or can recover from all but the hottest or most frequent fires. Indigenous Australians have used fire across the millennia to keep country healthy, flourishing and safe. Today, though, Australia is infamous for its out-of-control mega-fires, notably the record-breaking blazes that burnt for six months over the summer of 2019/20, decimating over 40 million acres in the southern states of Victoria and New South Wales. They don’t have these problems in the north because they still routinely burn. It’s been this way for thousands of years, and now there are Aboriginal Land Councils to help manage country the way the old people did.

“It’s all up to the Traditional Owners here. They’ll light up the floodplains to get the grass down for hunting; then, when it grows back all green, it’ll bring the animals back.” Other intentional fires are lit in mosaic patterns, sometimes to clean up country, sometimes to preserve areas as part of Australia’s Carbon Credit Unit (ACCU) scheme. “They’re protecting sections from being started unintentionally, from things like lightning etc. Then the money they earn sequestering carbon goes back into things like helis and other resources for land care – so essentially it’s going back into country.”

On his days off, Jeremy goes fishing with the rangers. “Yep, we’re flying into pristine, untouched spots all the time. And sometimes for work – apparently tomorrow we’ve got a Mangrove Jack survey… well, that sounds like a shit job!” he laughs. On other days, they’ll fly out, shoot wild cattle and buffalo, and then sling a beast back into the local community.

It’s an enviable lifestyle and a diverse range of flying in some of the best parts of Australia. Jez agrees, “It’s a lot. It’s a big job. When it’s busy, we’re never home, that’s for sure.”

“I’ve been very fortunate, I think, in my career. I’ve pretty much stepped straight into an R44 and had work every day with great workmates. I’ve moved up the ranks fairly quickly and sharpened my skills by doing challenging work. It’s been great. It’s definitely been a journey getting to where I am today, and it’s been totally worth it.”

Jeremy plans to continue evolving – into a better pilot and bigger platforms. “I’d love to get onto a good firefighting crew down south and fight the big ones, so fingers crossed I can get there one day.”

But for tonight, he’s happy to crawl into his humble but cozy bed on the floor. “It’s hot, it’s tough, but it’s a job that I love, and right now, I wouldn’t change it for the world.”

First published in Issue 154 of HeliOps Magazine